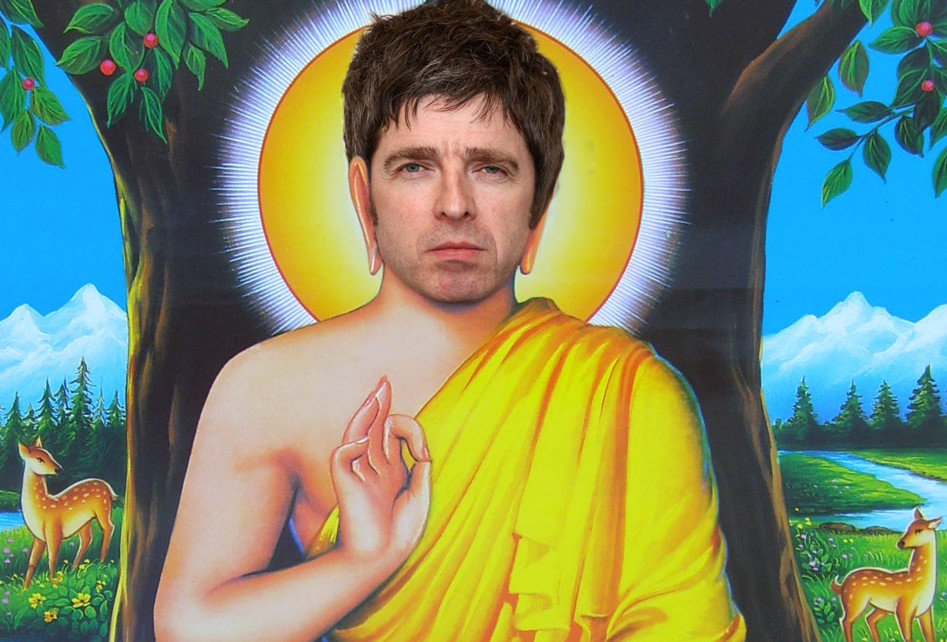

One of the great sages of our time, Noel Gallagher (yes, I’m being sarcastic) recently commented on how we need politics with cross party census.

“These days, my own view is that if they truly, truly wanted to f****** better the lives of the people, surely they must all realise that a little bit of conservatism married with a little bit of socialism, married with a little bit of f****** UKIP and a little bit of Green and a little bit of Lib Democrats would be kind of perfect.” Noel Gallagher

As a statement it veers dangerously close to wisdom. Wouldn’t we all like to see our politicians work in unison? Pulling together to make policy that works for everyone, rather than booing at each other like a bunch of children at a pantomime? This is wisdom we can all perceive as being right – it just makes sense, and therefore couldn’t be more wrong. The problem is that utilising it depends entirely on finding the point of balance, but how do we arrive at “the measurement of this measure” (Zizek, 2008:99)? Here wisdom runs out of answers because it does not know itself.

An excellent sketch on Radio 4’s ‘John Finnemore’s Souvenir Programme’ highlighted the inconsistency of fables – (fables are tantamount to the basic unit of perceived wisdom). The story of the three pigs is investigated by a roving reporter, interviewing them regarding the threat to their lives posed by the wolf. The Pig who has made his house from straw relies on his humility. The pig who uses sticks reasons that by taking the middle way he invokes the fable’s narrative protection. The third pig builds his house from bricks because… bricks are what houses are made from.

Perceived wisdom is like an externally inflated bubble we live our lives in. Noam Chomsky describes how it insulates us from other world views in the media in the documentary Manufacturing Consent (1993). Referring specifically to the US current affairs programme ‘Nightline’, Chomsky highlighted a rule they have when booking guests which requires their viewpoint to be communicated succinctly within two minutes. The question is what happens if your view cannot be simply expressed in that time? What if you need to bring in other context and further data? You end up with an echo chamber that drowns out dissident voices with accepted wisdom. This is why the third pig does the right thing, but for the wrong reasons. It accepts preconceived wisdom that bricks are what you make a house from, there is no challenge to knowledge, there is no lesson learnt; the third pig is as stupid as the other two. All it has is hindsight.

This anti-wisdom position could seem cynical, but it is quite the opposite. Think of the MP expenses scandal – the approach of wisdom is to say, “Well there will always be a certain amount of corruption, its human (or bird) nature to feather your own nest”, so wisdom advocates a system that allows them to assign posts nepotisticly, but stops moats for ducks. I think that is fairly cynical. Alternatively you could accept this innate corruption more radically and say MPs are unpaid and it is up to them to make a living purely through their expenses, with all expenditure a matter of public record. The system would be self regulating, akin to Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon, with each MP scared witless of their accounts being called into question by their fellows.

The Centralist Dilemma

For the past 20 years or so we have seen the political parties all converge on the center. That’s a good thing though, isn’t it? Positionally it is most reflective of the nation’s range of voices, it is balanced and moderate. It is also bland, mediocre and indecisive – basically what the Liberal Democrats are supposed to be for. However, since Tony Blair discovered the ‘third way’, as a nation we have become sucked into the centralist dilemma.

We don’t want to spend billions on four nuclear submarines, but we don’t want to lose the defense of mutual annihilation either. We need the middle ground of two nuclear submarines, or a few dirty bombs. We want better public services, but less taxation, the middle ground is to make services more ‘efficient’. We don’t want UKIP’s complete abandonment of environmental policy, nor the Green’s plan to phase out fossil-fuel energy generation and nuclear power. We need a middle ground where we only build wind turbines where they won’t ruin the view, phase out coal, burn up all the gas we can find, build a dozen nuclear power stations in Scotland, and continue to fail meeting internationally agreed targets, because the last thing we want to do is lower our emissions first in this Mexican stand off – there’s a recession on!

The ecological crisis is an interesting point of debate here since wisdom can only operate in hindsight, so any action we take can only be unwise. If we act and avert the disaster our actions will appear pointless, and wisdom would decree them to have cost too much, that the disaster was never going to happen and it was human arrogance to think we could impact a planetary system. If we do nothing and civilisation (and indeed life in general) is lost wisdom will say human arrogance destroyed everything. Worse still if we act in a lackadaisical manner, talking a lot about saving the planet but achieving nothing, wisdom will say that it was human stupidity.

By nature I am very much a pragmatist, however I’d like to see some positive idealism (someone to say ‘we can make things better’ and actually try, without blaming previous governments, or immigrants, or business for our woes – ie I’d like to see the Greens do well). What we don’t need is another populist coalition, which leads to voters being alienated from multiple parties when things inevitably go wrong (or, more accurately, simply change), the system can only cope with one ‘bad guy’ at a time. And the very last thing we need is any wisdom.